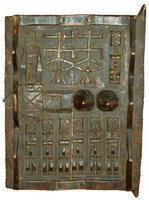

Dogon Door

Kate and I pushed out the gate of Mac's Refuge, scattering the tall, elegantly-turbaned sword and blanket sellers in a cloud of Saharan dust. We stooped slightly under the weight of our backpacks, our CFA (Communaut Financiaire Africaine) notes hidden in pouches strapped around our waists. I had a Dogon carved door tied onto my orange backpack, which made maneuvering even more awkward.

My Dogon wooden door featured rows of carved crosses and a pair of very perky breast-like appendages. It wasn't a door that had really been used in a Dogon mud hut (many of the beautifully-designed doors had been removed from the doors and windows of the traditional huts and replaced with corrugated tin, since they could be sold to tourists for a decent sum), but I didn't care and in fact preferred that I was not removing yet one more original door. Also, the door had been carved by a Dogon person in a traditional style, and though it was carved specifically for tourists, I thought it stunning.

My Dogon wooden door featured rows of carved crosses and a pair of very perky breast-like appendages. It wasn't a door that had really been used in a Dogon mud hut (many of the beautifully-designed doors had been removed from the doors and windows of the traditional huts and replaced with corrugated tin, since they could be sold to tourists for a decent sum), but I didn't care and in fact preferred that I was not removing yet one more original door. Also, the door had been carved by a Dogon person in a traditional style, and though it was carved specifically for tourists, I thought it stunning.

I had carried this door over dusty tracks from mud village to mud village nestled in the Dogon escarpment, and past crowds of running, dust-and-snot-streaked, swollen-bellied kids. This door had slept on mud roofs in the cool of the Sahelian night, and awakened to bright sun and a view of a woman bent at a right angle sweeping a nearby roof after threshing millet. It climbed a ladder down to a hard-baked mud courtyard where breakfast fritters sizzled in oil. It strode past two boys herding goats and playing with a stick and old tire. It jiggled in a donkey cart led by a bearded old man who sung lengthy greetings to everyone he passed, asking how was their mother, and their father, and their children, and their sisters, and brothers, and their aunts and uncles. It had ridden in crowded lorries, crossed the Niger in a ferry on the way to Djenne.

My Dogon door had come this far with me, and I was determined to board a bush taxi to Gao with it, to bring it with me as far to the edge of the Sahara as I could go.

My Dogon wooden door featured rows of carved crosses and a pair of very perky breast-like appendages. It wasn't a door that had really been used in a Dogon mud hut (many of the beautifully-designed doors had been removed from the doors and windows of the traditional huts and replaced with corrugated tin, since they could be sold to tourists for a decent sum), but I didn't care and in fact preferred that I was not removing yet one more original door. Also, the door had been carved by a Dogon person in a traditional style, and though it was carved specifically for tourists, I thought it stunning.

My Dogon wooden door featured rows of carved crosses and a pair of very perky breast-like appendages. It wasn't a door that had really been used in a Dogon mud hut (many of the beautifully-designed doors had been removed from the doors and windows of the traditional huts and replaced with corrugated tin, since they could be sold to tourists for a decent sum), but I didn't care and in fact preferred that I was not removing yet one more original door. Also, the door had been carved by a Dogon person in a traditional style, and though it was carved specifically for tourists, I thought it stunning.I had carried this door over dusty tracks from mud village to mud village nestled in the Dogon escarpment, and past crowds of running, dust-and-snot-streaked, swollen-bellied kids. This door had slept on mud roofs in the cool of the Sahelian night, and awakened to bright sun and a view of a woman bent at a right angle sweeping a nearby roof after threshing millet. It climbed a ladder down to a hard-baked mud courtyard where breakfast fritters sizzled in oil. It strode past two boys herding goats and playing with a stick and old tire. It jiggled in a donkey cart led by a bearded old man who sung lengthy greetings to everyone he passed, asking how was their mother, and their father, and their children, and their sisters, and brothers, and their aunts and uncles. It had ridden in crowded lorries, crossed the Niger in a ferry on the way to Djenne.

My Dogon door had come this far with me, and I was determined to board a bush taxi to Gao with it, to bring it with me as far to the edge of the Sahara as I could go.